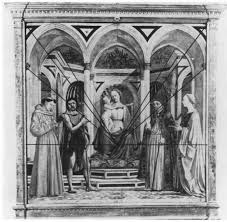

The best way to understand the difference between Gothic and Renaissance painting is to compare two altarpieces now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence: Giotto's Ognissanti Madonna Enthroned (1310) and Domenico Veneziano's St. Lucy Altarpiece (1445). We talked about the Ognissanti Madonna in the last blog and this blog will be dedicated to Veneziano's Madonna Enthroned with Saints, called the St. Lucy Altarpiece.

It was made as the central altar painting for the small church of Santa Lucia dei Magnoli on the other side of the Arno from the Duomo on Via dei Bardi in Florence:

| ||||||||||

FRANCIS, ST. JOHN the BAPTIST, the MADONNA, ST. ZENOBIUS, and ST. LUCY.

Unusually so, every predella panel here has survived, one for each of the figures, and we will look at those later. For now, let us examine what makes this a RENAISSANCE ALTARPIECE rather than a GOTHIC one.

1) There are still Gothic pointed arches in the scene over the four saints, but the pink faux marble arches for the niches and over the Madonna are rounded, a display of the RENAISSANCE preference for rounded arches in architecture and a Florentine preference for colored marble, such as on the Duomo and bell tower.

1) There are still Gothic pointed arches in the scene over the four saints, but the pink faux marble arches for the niches and over the Madonna are rounded, a display of the RENAISSANCE preference for rounded arches in architecture and a Florentine preference for colored marble, such as on the Duomo and bell tower.2) Although the Madonna is still enthroned with Child on her lap, she is no longer up in a gold leaf heaven but is in a courtyard with a natural sky and orange trees. LIGHT IS NO LONGER GOLD LEAF, BUT NATURAL LIGHT of the world. We even see a shadow cast by that light above the head of the Madonna; the line of the shadow angles down towards the Child, who is thought of as the LIGHT OF THE WORLD.

3) THE ALTARPIECE has a CONSISTENT NATURAL LIGHT SOURCE. The shadow cast by the architecture behind the throne is consistent with the shadow cast by the light on all of the figures of the saints. If you look at the feet of St. John the Baptist, Zenobius, and Lucy, the shadow falls to the left of the figure, which indicates a light source coming from the right in the scene. The shadow over the Madonna's head also seems cast from a light source coming from the right.

There is one discrepancy in the natural light source here that can be explained by the name of the church. St. Lucy's face is bathed in light, as though a spotlight were trained on her from the front of the altar. If the natural light were completely consistent from the right, some of her face would be

in shadow. But she is a saint associated with eyesight and light.

She holds in her right hand the palm of martyrdom and in her left a plate on which we can barely see two eyes, one of which is indicated by the point of the palm frond. According to the Golden Legend, she was a virgin at the end of the 3rd century who dedicated her life to chastity and Christian faith. She had a suitor who wanted to marry her because of her beautiful eyes, and to demonstrate her commitment to the Virgin, she plucked out her eyes and sent them to him. The Madonna rewarded her faith by restoring her eyesight, hence she has two sets of eyes here, the ones on the plate and the ones in her face. Her name, LUCIA, comes from the root of the Latin word, LUX, LIGHT, so the extra play of light over her face is done on purpose to remind the viewer of her star role as the saint of this church, Santa Lucia.

Domenico Veneziano, as his name implies, was from VENICE, and the light we see in this painting is the bright light of VENICE, playing across the surfaces of the people, the trees, and the architecture. The painted architecture is also reminiscent of the pink ISTRIAN STONE of actual Venetian architecture, so his altarpiece reproduces the colors and light of his native town, as well as the green marble he saw in Florence. As a consequence, the viewer experiences a new pastel world, where the pinks and greens enliven the entire scene.

Only the red cloth of St. John the Baptist, which he wears over the animal skin common to images of St. John to remind us of his life in the wilds of the desert, is symbolic of the Florentine dyeing industry and the red cloth for which it became famous.

There is also a curious juxtaposition of St. John's pointing hand which appears in front of the colonnette holding up an arch which seems to be over his head and perhaps in front of him, too.

5) THE HOLY FIGURES ARE THE SAME SIZE or NEARLY THE SAME SIZE as the SAINTS.

The Madonna and Child in this Renaissance altarpiece are only slightly bigger than the saints who share the same space with them. They are not up in heaven in a holy realm separated from the other figures but rather are portrayed as humans in the same way that the saints are. The Child is a naked little boy for this reason, his human sacrifice is accentuated, and he poses as many children might, on the lap of his mother in the center of the space.

Because the saints share the same space, light, and proportions as the holy figures in this scene, this type of altarpiece is called in Italian, a SACRA CONVERSAZIONE, a SACRED CONVERSATION. John faces the viewers to draw them into the conversation with the central holy figures of the Madonna and Child, but also to draw us into the conversation with the other saints, who

gather in a semi-circle around the central figures.

What he gives us is a pleasant, light-filled room with a throne accessible by the two steps inlaid in green, white, and pink marble just like the inlaid marble colors of the Florentine main church. We are invited into the space by St. John where we can get to know the saints as human beings. St. Francis reads his book and meditates with one hand on the stigmata of his chest, John speaks, Zenobius blesses us and holds his bishop's staff and wears his bishop's miter on his head. Lucy points to her eyes (she wasn't martyred that way, she was executed by sword later) and seems to look towards both John and the Child. Her pink robe falls into natural folds which reflect and absorb the light.

6) ALL OF THE FIGURES seem to respond to GRAVITY and have EXACT ANATOMY even under the drapery. The drapery appears to fall in natural folds and to show the volume of the bodies underneath it. The figures have natural weight and appear to be living, breathing beings, rather than stiff, bulky, unearthly creatures with wings. The holy stories have come down to earth, literally.

7) As in the GOTHIC altarpiece, there is an emphasis on SYMMETRY: two saints on either side of the central figures, a mirroring of the architectural pieces on both sides. THAT SYMMETRY continues as an element characteristic of RENAISSANCE ALTARPIECES to give the scene harmony.

8) NEW in the RENAISSANCE, though, is the ARTIST's SIGNATURE. The self-consciousness of the artist as the creator of the work is a RENAISSANCE theme, not a GOTHIC one.DOMENICO VENEZIANO signs his work on the bottom stair rung of the Madonna's throne. Giotto would not have dared insert himself into the holy heaven of his Madonna, but Domenico is thinking like a businessman and the painting is as much an advertisement for his future employment as it is a holy scene to be idolized in the church in Florence.

The inscription on the step says:

Opus Dominici De Venetiis Ho(c) Mater Miserere Mei Datum Est

LEFT BACK LEFT SIDE FRONT RIGHT SIDE

Work of Domenico di Venezia This Mother of my Miseries Is Given

The artist is offering up his painting to the Madonna with a prayer. He is proud of his work and

is also aware of its religious efficacy.

PREDELLA:

The predella scenes are vignettes of the figures standing above them.

From the LEFT:

From the LEFT:ST. FRANCIS RECEIVING THE STIGMATA and

St. JOHN CHANGING INTO ANIMAL SKINS

(both in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.)

Francis on the left looks up in the sky at the red cruciform figure of Christ as he receives the wounds in laser lines from that seraphim-encircled shape while his companion, Leo, shades his eyes from the blinding light of the vision. The infinite landscape with natural sky is like other Renaissance altarpieces of the Quattrocento (15th century), but the pointy rock forms are vestiges of Gothic ways of portraying landscape. Those same pointy rock forms are seen in the predella next door, the scene of St. John in the desert. At the same time Veneziano displays his knowledge of anatomy (a Renaissance interest) with the pectoral muscles of the nude body of St. John.

St. John and Francis both face to the viewer's right, toward the Madonna in the center.

The central panel of the predella is twice the size of the others, for the importance of the Madonna, whose Annunciation scene is shown next:

ANNUNCIATION OF THE VIRGIN (now in the FITZWILLIAM Museum, Cambridge, England)

The one-point perspective in this small panel is beautifully rendered, as is the light-filled courtyard between angel and Madonna. The Madonna is in the ACCEPTANCE STAGE, with both hands crossed on her chest.

ST. ZENOBIUS restores to life a child thought dead

after being run over by a cart in a street in Florence. A crowd

gathers while Zenobius lifts his hands in prayer while kneeling

left toward the Madonna.(also in the Fitzwilliam)

The very last predella panel on the right is the scene of St. Lucy's Martyrdom. The saint kneels facing left while the executioner steadies her head:

This panel is in the State Museums of Berlin. Up on the balcony Diocletian gives the command for her execution. In none of these predella panels is there a gold-leaf background. The sky is depicted and earth is a light-filled realm with natural-looking figures sometimes in urban architectural settings. The emphasis is on the human world of the saints and their connections to the holy figures they pray to for help.

Since Lucy is the patron saint of sight, how appropriate that Veneziano paints a world of visible beauty for the viewers of his altarpiece.

A spectator cannot leave the world Veneziano has created without being nourished by the beautiful light, color, and human beings he presents. That we hear St. John's voice and breathe the air in this Queen's court only adds to the magic.

No comments:

Post a Comment