As we mentioned in a previous blog on Luca della Robbia's Cantoria, some discussion should be given to the order in which the panels were sculpted. Luca's Cantoria for the Florence Cathedral (now in the new Museo dell'Opera del Duomo in Florence) was produced between 1431 and 1438.

The documents that survive tell of payments in 1434 to Luca for two large panels and two smaller ones, which suggest that two panels from the front were finished by then and the two side panels which are smaller in size.

Which front panels were sculpted first then? Since the panels were carved separately from the architectural console holding them, the inscription words do not tell us the order of the sculpting, just the order of instruments mentioned in Psalm 150. He did not begin with the TRUMPETS.

As the scholar Gary Radke has pointed out in the exhibition volume Make a Joyful Noise (2015, pp.11-49), one way to approach the problem of chronology is to look at the quality of carving and the intricacy of the relief depth carved. His belief that the Tambourine panel was carved first is a good one for just those reasons. The figures are flatter than in all of the other reliefs, the intricacy of overlapping marble parts is simpler, the children are, in spite of the LATIN, CYMBALIS BENE SONATIBUS, staid and restrained, hardly moving and hardly detached from the background. A beginning sample of careful, uncomplicated carving.

The children (some with wings, so presumably angels) are very young, keep their arms contained within the same section of marble used for their bodies, and form a tight, regularly layered group of three distinct reliefs, from high (carved further away from the background) to low (carved close to the background) without much interaction between the figures. The framing figures at either side set the curtain ends for the main child in the center who wears a long wreath and whose tambourine sticks out furthest. These are simple, clear figures illustrating the instruments mentioned below them.

What becomes apparent when we compare this panel with the others at the bottom and top is that this first group also represents a certain type of RHYTHM: SLOW RHYTHM.

If we take rhythm into account, and assume that Luca worked on the SLOW RHYTHM panels first, the next likely candidate for chronological order is the panel in front next to it, that of the CORDIS ET ORGANO (STRINGED INSTRUMENTS AND ORGAN):

In this panel are nine small children instead of seven, but the arrangement of them is similar, with bodies and heads of the same height carved in variations of low to high relief. These children encircle a central figure, this time a seated female who plays the portable organ. The sculpting is slightly more complex with the added instruments of harp and lute and the left leg of the far left figure separated from the other leg with more air between the two. Some air exists also between the legs of the chair and the legs of the girl with portable organ, but essentially the setup of the figures is like that of the TAMBOURINE panel, far left figure facing in to center, far right figure facing out to the viewer. And most importantly, apart from the projecting leg of the left figure, the figures hardly move, the RHYTHM is SLOW or STOPPED. In both panels some of the children do open their mouths to sing, but the appearance of the new musical instruments of portable organ, harp, and cittern do not make the figures move more quickly in the space; the instruments function like the four tambourines in the panel to the side of it, as visual signs for the words written below, CORDIS ET ORGANO.

If we look closely at the three left figures in this panel, we are given a hint for the next panel carved, the side panel of the SCROLL:

Here in both we find the same motif of a low-relief (bas-relief) face in the left background behind two figures who drape arms over shoulders to join in the singing. Luca transfers this idea to the presentation of the choirboys in the SCROLL panel, where a hand juts out over the shoulder of the second-to last left figure and the hand appears over the right shoulder of the singer holding the left edge of the scroll. He has changed the ages of the participants to adolescents now, but the idea of joining together in music and song is continued from this front panel to the side panel, making a transition from second panel produced to third in the chronology.

We have discovered the first three panels sculpted, then, and that would make the fourth an easy choice, since we know there were two large and two small finished by 1434:

In all FOUR of these early panels, the RHYTHM is SLOW. The figures stand and perhaps open their mouths or hold an instrument or CODEX or SCROLL, but apart from the foot beating time, or the leg akimbo, they do not move in the sculpted space very much. Their arms may crook at the elbow, but their heads remain on a line, high relief to low, and they stand as if the music-making has transfixed them. The tentative touching of hand to shoulder is symbolic of Luca's own tentative trying out movement and implied space for arms behind other figures. The figures in the CODEX panel are also adolescents and younger boys, and we have pointed out the bullying going on in the panel, but that is not carried out with much motion.

Luca continues to be tentative in carving movement in the next two panels he must have carried out in the front because those, too, have SLOW RHYTHM. They are the panels of PSALTERIO and CYTHARA, the Psaltery and Cittern panels:

5-Psaltery 6-Cittern

The figures in these panels are adolescents and infants; they stand or sit, they sing and hold instruments, and the relief varies from high in front to low in the background, much as they were arranged in the first four panels we have discussed. The rounded cheeks of the adolescent at left with child below (who has identical rounded cheeks and small mouth) connect this panel to the previous two smaller side panels:

The framing figures on the sides are vertical elements that keep the viewer's eye focused on the central activity in both large panels. The emphasis on the vertical pleats in the musicians' robes also contributes to the stiff nature of the movement. The players stand and sometimes sing, sometimes play, sometimes play as they sing, but rarely exit the borders of their own bodies. They are stopped to play the psalm music.

Only the small putti in the cittern panel begin to change the motion and rhythm of these panels by moving their arms to point to the players of the citterns above them. Their bodies also project more fully below and outside the high relief of the central figures.

These male and female participants sing and play IN PLACE, demonstrating harmony in their composure and their instruments for their audience. The instruments they play are ALL instruments of SOFT SOUND and SLOW MUSIC: PSALTERIES and CITTERNS in the upper sphere, ORGAN, HARP, LUTE, and TAMBOURINE in the lower sphere. THESE front panels, together with the side panels are the FIRST 6 to be produced by LUCA della ROBBIA, panels representing SLOW MUSIC, SLOW MOTION, SOFT SOUNDS.

While it is possible that Luca worked simultaneously on several panels at once, and it is possible that workshop hands account for some of that work, the general principle of soft instruments and slow motion being created in the earliest of his panels on the Cantoria works for establishing a chronology. Whether he planned these central front panels to all be arrested motion and the others to be full motion is never written down. Neither is it written down the influence he exerted on Donatello or Donatello on him. However, it seems likely that the four remaining panels in the front are the last to be completed, and it seems likely that they are given a faster RHYTHM and that they demonstrate that RHYTHM with LOUDER INSTRUMENTS under the influence of Donatello's arriving on the scene to begin his own Cantoria in 1433. From this point on Luca's figures are filled with movement and liveliness and his own original arrangement of figures within panels changes in competition with the older master.

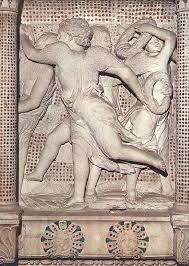

We have only to look at the next panel I believe is seventh in the chronology, the CYMBALIS IUBILATIONIS, the Clashing CYMBALS and compare it with the right side panel of Donatello's

Luca takes the rushing infant in the middle of Donatello's scene and transports it to the center of the CLASHING CYMBALS scene. The child has no wings and holds cymbals about to clash in his hands, but his feet are placed with weight on right foot, left foot swung back, exactly as the putto in Donatello's Cantoria begins the dance underneath trumpets in his side panel. What seems clear, too, is that Donatello's sense of infinite relief space sets a spark in Luca's figural arrangements. Luca no longer requires the side figures to turn inward to the center. The march of the cymbal players is from left to right, implying a space to the right and to the left that they are marching through and onward, much as the children in Donatello's also imply a marching through space.The overlapping of figures' legs, cymbals and hands and heads is all new to Luca, much more exciting and complex, stimulated by the layers of motion implied in the Donatellian example.

The same is true of comparisons of movement in the last three panels, 8, 9, and 10. The RHYTHM is speeded up and the instruments play LOUD MUSIC, PIPE and DRUMS, and TRUMPETS. In each of these next panels the figural arrangements continue to be complex and in quick motion, requiring five layers of bas-relief, from high to low in an intermingling of instruments and dancers. Here we also find less emphasis on the framing figures to focus our attention on the central ones. Side putti distract from the main scene and imply infinite space and movement.

8 - TABOR AND PIPES, TIMPANO

10 - CHORO - DANCE

And in every last panel we see the influence of Donatello or that of Luca on Donatello:

Look at the LEGS, though! Even with the absorption of Donatello's movement into his scenes, Luca has not understood the basic concept of step sequencing. The figures at the front of this dance, the ones in highest relief have a left leg on the ground, and are about to put weight on the right leg. They are not in sequence with each other or in sequence with the side figures whose feet either touch the ground or are lifted up high. Even if these feet were meant to represent a dance motion done in unison, they fail in the lack of symmetrical leg placement. If the circle is meant to present the continual motion of the dance, it fails, too, because it does not describe what Donatello understood as the core of perpetual motion: STEP SEQUENCING.

If Luca had given us the stepping we see in Donatello's Cantoria, we would have no problem imagining this circle in a continual eternity. But we have to ignore his FEET and look at his FACES: they are the carriers of this merriment and because of their beauty, we feel the joyful praise he wants to convey from Psalm 150.

But it is in DONATELLO's FEET that the viewer feels the RHYTHM of the PSALM and the future of movement in art. It is DONATELLO'S figures who carry forward the banner of joyful praise that excites every time it is replayed on the Cantoria for the Duomo, as though a Renaissance video.

And it is not until Botticelli's Mystic Nativity that we see a similar circle dance of angels where the stepping follows Donatello's precept for an eternal rondo:

The chronology of Luca's panels for the Cantoria, then, seems to be a sequence of 6 slow panels, followed by four quick ones, where the skill of the sculptor, for the most part, improves with age.

He begins lower center, moves to the side panels, then returns to the upper middle, finishing with his own circle dance by completing 7,8, 9, and 10. His own work sequence is not meant to convey a continuum. He wants us to stop and start, and stop again, to admire the particular sound for every panel. We see him give us a slice of rhythmic life in every scene and we pause to realize the connections he forges between words and musicians. If Luca had not had Donatello's Cantoria across from his, we would have been enchanted by his beautiful rendition of Psalm 150.

He begins lower center, moves to the side panels, then returns to the upper middle, finishing with his own circle dance by completing 7,8, 9, and 10. His own work sequence is not meant to convey a continuum. He wants us to stop and start, and stop again, to admire the particular sound for every panel. We see him give us a slice of rhythmic life in every scene and we pause to realize the connections he forges between words and musicians. If Luca had not had Donatello's Cantoria across from his, we would have been enchanted by his beautiful rendition of Psalm 150.As it is, we look at Donatello and want Luca's angels to move faster.

No comments:

Post a Comment