FIRST WORK: LORENZO GHIBERTI'S JACOB and ESAU -3RD BRONZE PANEL, left door

FLORENCE BAPTISTERY - EAST DOOR FACING THE CATHEDRAL - 1425-52

ESAU IS A HAIRY MAN

STORY OF JACOB -The Jacob story in Genesis (Chapter 25-27) as interpreted by Ghiberti at first glance seems to subvert the tale in the Bible.

Biblical version:

The Biblical narrative is one of birthrights and twins. Esau is the firstborn twin son of Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob the second twin. Rebecca favors Jacob because when she is pregnant God tells her:

"Two nations are in thy womb, and two manner of people shall be separated from thy bowels; and the one people shall be stronger than the other people; and the elder shall serve the younger."

She also prefers Jacob, her second-born, later in his life, because she doesn't like the wives that Esau has chosen to marry, "which were a grief of mind unto Isaac and to Rebekah." Isaac, the father, though, prefers Esau because Esau grows up to be a hunter who brings him venison to eat.When Isaac gets close to death and is nearly blind, he calls Esau to him and tells him to go out hunting to get venison and that after the meal he will give him his blessing.

Rebecca hears this plan and thwarts it by having Jacob obtain young goats which she quickly cooks for him to give as a meal to Isaac. Isaac eats the goats, then is prepared to give the blessing. He can't see Jacob but he hears his voice and thinks it is Jacob, his second son, not Esau, his firstborn. He is suspicious. The clue he searches for then to determine the identity of the child is the hairyness of his skin. Esau is a hairy man and Jacob "smooth." In order to fool Isaac into thinking he is blessing his firstborn, Rebecca tells Jacob to cover his hands and neck with the "skins of kids" and to wear a raiment of Esau's left in the house. Jacob knows he is lying to his father and is afraid his father will curse him if he finds out. But Isaac feels the "hairy" skin of the goats on Jacob's hands and smells the smells of the earth or the hunter on the clothing of Esau that Jacob is wearing and he believes that he is blessing Esau when he says:

"God give thee of the dew of heaven, and the fatness of the earth, and plenty of corn and wine; let people serve thee, and nations bow down to thee; be lord over thy brethren, and let thy mother's sons bow down to thee, cursed be every one that curses thee, and blessed be he that blesseth thee."

GHIBERTI's Panel (THIRD PANEL from top, LEFT EAST DOOR, FLORENCE BAPTISTERY, 1425-52:

Ghiberti's version:

The bronze panel follows several episodes from the Bible story: 1)Rebecca's conversation with God before the twins are born, 2) Rebecca on the birthing bed, 3) Esau's selling of his birthright to Jacob for a pot of porridge, 4)Isaac telling Esau he will be blessed if he goes and hunts, 5) Esau's leaving for the hunt, 6) Rebecca's instructing of Jacob in the deceit, and 7) Jacob's receipt of the blessing.

In the background and in lowest relief (that is, least protruding) are scenes 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6. In the foreground are scenes 4 and 7. Usually in Renaissance art works scenes that occur in the background are events that have taken place in the past, or earlier than those in the foreground. But that is not the case here for scene 5. Esau only leaves for the hunt after he has his meeting with his father, scene 4. Nor do the Ghiberti vignettes follow the usual Renaissance pattern of events depicted as though read from left to right in chronological order. Ghiberti, as a bronze panel artist, needs to fill up the space with the narrative and does not conform to chronology. He has the viewer jump around the space to read the events in chronological order. Scene 1 is on the right rather than the left. Scenes 2,3, and 5 are left to right in order, but 4 and 6 force the viewer to question what time in the sequence is represented.

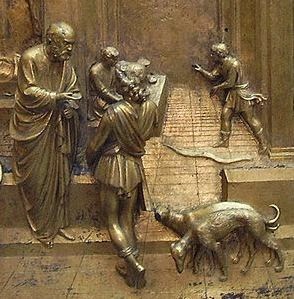

Jacob is not the central character in Ghiberti's panel, Esau is. The two twins are split in the space: in the foreground the dividing line is the actual line in the pavement, the perspective line that runs from the edge furthest forward in the panel to the back wall of the fictive building. Esau and Jacob are presented in high relief on either side of that line in the foreground, Esau stepping with his back to us on the left side of the line and further forward and Jacob kneeling on both knees on the right side.

Then in the middle ground, the twins are sculpted in lower relief again on either side of the line, this time Esau stepping forward on the right side, Jacob hidden sitting at table on the left side.

They are split a third time by one of the pilasters of the building on the right, with Jacob talking to his mother on the left side of the pilaster (does he have a dead goat in his hands?)and Esau leaping up the rocks with his hunter's bow on the right side of the pilaster. The spatial split emphasizes the division in the twins' inheritance and ambition.

Esau is the figure in the foreground with two dogs and with his back to the viewer.

(The dogs mirror the characteristics of the two twins; they are identical in breed, but one has curly hair and the other smooth). Esau is shown three times, once in the foreground in highest relief, once as the standing figure above the dogs where he has dropped his bow in hastening back from a hunt (in another episode of the story when he sells his birthright to Jacob for a bowl of pottage because he is so ravenous from the hunt), and the third time,

with his bow in hand,

running off in a landscape suggested by rocks and a tree, in the far

right background.

with his bow in hand,

running off in a landscape suggested by rocks and a tree, in the far

right background.This last image of him at the back of the panel in a different landscape keeps him in the distance, a distance meant to remind us of the long time it would take for him to go out and hunt a deer and return to cook it for his father. During Esau's long absence Jacob is able to serve his father a meal and receive a blessing in the foreground.

Esau in Ghiberti's depiction is not particularly hairy on his legs

(they are beautifully "smooth"), although the dog furthest forward is

rendered with curly hair that has texture and Esau himself has more and

longer hair (seen 3/4 view from the back) than Jacob on the right.

Isaac, the father, appears twice, both in the foreground. He stands left of the central line with beard and long cloak and instructs Esau before the blessing. He also sits on a bench to the right when he gives the actual blessing to Jacob.

Rebecca is depicted four times in the panel, once on the roof of the building in conversation with God about the birthright (she looks very pregnant here),

once in mid-ground telling Jacob what

to do to fool his father, and once in the foreground far right watching the blessing being

bestowed upon her favored son as he kneels before his father.

to do to fool his father, and once in the foreground far right watching the blessing being

bestowed upon her favored son as he kneels before his father. Rebecca here looks over at four women in a group conversation and in long gowns to the far left of the panel - are these meant to represent Esau's Hittite wives whom Rebecca doesn't like? (In her birthbed she also looks at them anachronistically with disdain.)

Rebecca here looks over at four women in a group conversation and in long gowns to the far left of the panel - are these meant to represent Esau's Hittite wives whom Rebecca doesn't like? (In her birthbed she also looks at them anachronistically with disdain.)

These four women are prominent graceful and feminine figures with curves revealed beneath their long drapery. The swaying of the drapery around them suggests dance movements in the space. Botticelli certainly looked at these figures when he conceived his three Graces; he chose to paint three instead of four, but in both groups there is one with her back to the viewer who steps on left foot with right leg out while the other women look in toward the group. The far right woman in both bronze and painting has her hair in a bun, and the far left figure in Botticelli's group tilts her head in the same way that Ghiberti's female second from left does.

Ghiberti ignores the moral for the beautiful and makes the figures of Esau, his wives, and dogs, the most attractive of all the figures in the panel. They are also in the highest relief (that is, least attached to the panel) and the eye of the beholder looks immediately to them. Esau's figure is closer to viewers who walk by the Baptistery East door than even more important figures such as Adam and Eve, who appear in the upper panels of the door.

Both Jacob's story and his panel are about deception and its rewards. The Biblical episodes that tell his story portray how the normal line of primogeniture can be manipulated so that the second oldest can hold the birthright. Jacob only gets his father's blessing by fooling him into thinking he is the firstborn and deserving of his father's words. He and Rebecca know they are changing Isaac's perception of the person by adding goatskin to resemble Esau's skin and clothes that smell like Esau's. The deception works, and Jacob then is head of the household. He has to leave the household immediately to avoid combat with Esau, but in the end, he is rewarded with his father's lands in perpetuity, according to the Bible.

But is Ghiberti's own preference for the original firstborn, Esau, the hairy man? His figure of Esau seen from the back in the center of the composition is one of the beauties of Italian Renaissance bronze sculpture.Ghiberti himself never again achieves such an elegant, poised, and proportionate male figure in the bronze doors or elsewhere. His Esau is the height of Renaissance sprezzatura, stepping easily into the space, keeping his dogs under control, reaching for his father with composure, dressed in a Renaissance tunic and tights. He is the epitome of Renaissance beauty, the beauty that Ghiberti wishes to display as his art on the doors. Esau is beautiful, and nourishing because of his beauty, not because of his venison.

Ghiberti understands that beauty is nourishment (my phrase), but he knows artistic beauty is also deception, and that he must use deception in order to orchestrate the blessing of the viewer who walks by the piazza. (The originals were on the door until moved, in the 1980's, to the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo for cleaning and a future museum of their own.)

Ghiberti uses lines in the pavement that recede into space to give the viewer a sense of depth in the scene. He sculpts the building with three arches for several of the episodes of this story in order to deceive the viewer into feeling they have stepped into the biblical narrative as they look at the panel. And he deceives the viewer into thinking they are seeing real people in real history by making all the figures conform to the space and to each other. His drama is not lifesize, and yet seems so.

Is he giving prominence to Esau, the hairy man, to play up viewers' confusion about the twins' birthright? He knows his 15th-century contemporaries will expect the firstborn son to receive the patrimony in each family. He knows that in this story God and the mother changed the course of the usual inheritance line. Is he handing Esau a larger visual role than his brother's in the drama in order to undermine the Old Testament message?

(Ghiberti himself was firstborn and had two fathers, his natural one and an adoptive one who taught him the art of goldsmithing; that could explain the two Isaacs in this panel. Could it also explain an anxiety about the power of the firstborn being yanked away? a desire to make the case for the firstborn in spite of the Biblical story?)

The only statement in the panel that counteracts the strength of Esau's figure is the barely-visible bow dropped directly to the right of the youth. Ghiberti's artistic statement here is that Esau "dropped the ball" in letting Jacob buy his birthright; his bow on the ground reminds us that Esau gives his birthright away after his father decides to bestow it. Esau and his father share responsibility for the blessing being given to the second son.

Isaac's confusion as to which son he's touching becomes the viewer's confusion as to which son is portrayed more prominently. Which twin is the beauty in the middle left with the dogs? Is Ghiberti worried about the story of the second son receiving the birthright being shown on a building meant for baptizing?

Ghiberti was also an author as well as a sculptor and he writes a book called Commentarii that gives his idea of what art should accomplish. One of his concerns is the "eye that moves," the viewer's eye that moves as a person walks by any art work but, of course, particularly his panels on the doors of a prominent building in a prominent piazza, the Florentine Baptistery in the Florentine Cathedral piazza. Consequently, one can walk past Ghiberti's Jacob panel, and from every angle the figure of Esau has beauty that stands out; Ghiberti takes into consideration that his figures will be seen from left, from center and below, and from right, and he accommodates the wishes of the viewer by making his relief figures beautiful to behold from every angle.