In the previous blog entry (A) we discussed the main section of the Pesaro Altarpiece painted by Giovanni Bellini probably in 1475, with its subject, the Coronation of the Virgin with Saints. In this blog entry I wish to talk about the gable painting that was originally above the main section and the predella panels that are still beneath it in the museum.

The gable painting, now in the Vatican Museums, is a scene of the Deposition, the taking of Christ's body off the cross before lowering it into the grave. His body perches on the edge of the sarcophagus while Joseph of Arimathaea holds it upright before placing it in his own tomb, a gift he gave to Jesus. Nicodemus, a dark-bearded figure standing above the rest, holds the ointment jar from which Mary Magdalene has taken the oil with which she is caressing Christ's hand.

The solemnity of this scene of death is presented by Bellini "di sotto in su," from below looking up,

because he knew that the viewer of the altarpiece would be looking UP at the gable above the

main scene. (For the questions about whether the Deposition or Compianto was originally intended

for this altarpiece, see Rona Goffen, Giovanni Bellini, Yale, 1989; she thinks it was.) Normally in Renaissance art we would expect this story of the end of Christ's life to be juxtaposed with a story from the beginning, something like the Nativity or the Adoration of the Child, so that we could compare the alpha and the omega, the beginning and end, and learn from that something about the length of Christ's whole life. This altarpiece, instead, places the image of death above a Coronation scene that doubles as a sacred conversation piece with the four saints who are attending the Coronation. We are reminded of the sadness of Christ's death just above the joyful experience of Mary's crowning as Queen of Heaven. Instead of a measurement of Christ's days on earth, though, the altarpiece is a reminder of the shortness of life and how successes such as the crowning of a Queen should be enjoyed while they last.

The gable panel and the predella panels (on the bottom of the altarpiece) tell stories of the saints depicted in the main altarpiece and they contribute to the emphasis on the importance of CARPE DIEM as a theme for the altarpiece. When the gable was together with the Coronation, the whole altarpiece would have been very large, as shown below in a conjoining that took place in 1989 for a special exhibit.

The date of the altarpiece has been disputed by scholars since there are no extant documents

to tell us anything about the commission, but it is generally dated between 1471 and 1483. In my blog entry on the Coronation, I have given reasons to date it to 1475. We do know that it was to be placed in the Franciscan church of San Francesco in Pesaro on the main altar, which explains why Saint Francis appears in the main section and the predella. I think Costanzo Sforza had the altarpiece made in celebration of his own wedding which took place over five days in May of 1475.

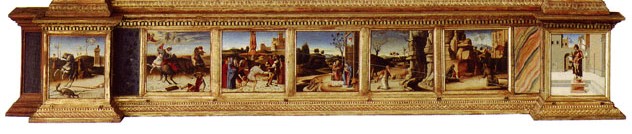

The predella panels are wonderful scenes to be studied in and of themselves.

From the left the subjects are:

Killing of dragon St. Paul's St. Peter's Nativity St. Jerome St. Francis St.Terence

by St. George Conversion Crucifixion Flagellation Stigmata

The landscape runs in a continuous sweep behind the figures in the predella scenes and gives them

a coherent whole. The two saints furthest left and right are warrior saints meant to remind us of

Costanzo Sforza's career as a condottiere, while the five scenes in the center correspond to the

saints directly above, that is, St. Paul's Conversion for St. Paul, St. Peter's Crucifixion for St. Peter,

the holy family for Mary and Christ above, St. Jerome's self-flagellation for St. Jerome, and The

Stigmatization of St. Francis for St. Francis above.

From the left:

Killing of dragon by St. George:

Both this scene, where George breaks his lance in the dragon on behalf of the Princess who stands behind on the left, as well as the next scene of St. Paul's Conversion, feature a horse who rises on his

back legs in the same manner as the horse does in a medal of Costanzo Sforza of 1475:

St. Paul's Conversion

This Conversion scene is set below the figure of St. Paul in the Coronation. In the predella panel Paul is on the ground, having been hit by the truth of the light so forceful that he is knocked from his horse. He looks up to the vision of Christ in the sky. From this moment on Paul is no longer a Roman Jew; he instantly becomes a Christian believer. He is wearing the armor of the Roman army since he was a Roman soldier before his conversion.

In the main altarpiece Paul stands next to St. Peter, so the subsequent predella panel is the story of the Crucifixion of St. Peter:

St. Peter was crucified upside down because he didn't think he was worthy to be crucified in the same manner as Christ. His upside-down Crucifixion takes place in front of a building meant to resemble Castel Sant'Angelo in Rome so that the viewer will understand where he was martyred. What is unusual in this scene, however, is that not only is Peter being crucified, but he is being stoned by several men, one of whom, dressed in pink and seen from the back, holds a stone in his right hand.

As Rona Goffen has pointed out in her book on Bellini, the Stoning of St. Peter is not a story from

the usual stories about St. Peter's life recounted in Acts in the Bible. She astutely connects this

predella stoning to the stoning that took place in 1471 in Rome of the newly elected Pope in that year,

Pope Sixtus IV. Sixtus survived, but it is probable that Costanzo Sforza was present in Rome in that

year and witnessed the stoning of the successor of St. Peter. Goffen suggests there are two portraits

over on the left of the scene, but she does not guess at the identities of them:

I think the dark-haired fellow, who looks around 27 years old, is Costanzo Sforza himself, and the cardinal standing next to him in red is Giuliano della Rovere, later Pope Julius II, a great patron of the arts even when he was Cardinal. As Sixtus IV's nephew, Giuliano would have been present at the stoning of his uncle, too. If we reverse the profile portrait of Costanzo on his medal cast in 1475, it

looks much like the dark-haired man here.

And Giuliano della Rovere's medal portrait resembles the Cardinal in the Stoning scene.

Costanzo and Giuliano are related by marriage, and Giuliano would have come to Costanzo's wedding in 1475, four years after they both saw the Pope being stoned in Rome. This panel unites them as witness figures in an important event for the papacy.

The next predella panel is more peaceful, the Nativity underneath Mary and Christ in the main altarpiece.

Mary and Joseph in this scene look down at their newborn child in front of a manger with an ox and ass, and behind them winds a river through a lovely valley landscape. A star with red seraphim can be seen in the open gable of the manger with the sky beyond.

The next two saints in the main altar also have predella stories associated with them; they are St. Jerome and St. Francis:

Flagellation of St. Jerome. Out in the desert Jerome fasted and beat himself with a stone on his chest to atone for sins. In Bellini's version he kneels in white before a simple cross in front of a cave. In one hand he holds a stone and hits his chest with the other.

St. Francis' Stigmatization follows St. Jerome's self-flagellation:

St. Francis, in the story, was kneeling and praying near a church with his fellow monk, St. Leo, here shown reading a book on the left. They were in La Verna, the cliff location where Francis went to live with his followers. A red seraphim approached in the shape of Christ on the cross, and rays of light

from each of Christ's wounds struck Francis in the same places: one on each hand, one on each foot,

and one on the chest. Francis suffered the pain from the piercing wounds until his death two years after the event. Bellini does paint a church behind the saint, but it is not like any church at La Verna. Instead Bellini painted what he knew: the largest Franciscan church in Venice, its apse end with Gothic pointed arch windows, circled in the drawing below. Bellini reassures the viewer that this

predella is about St. Francis by painting in the Venetian church dedicated to Francis.

The final predella panel is of St. Terenzio, who holds a white flag with red cross and a model of Costanzo Sforza's castle, the Rocca Costanza, as it is known as today.

As explained in the previous blog, the presence of Costanzo Sforza's pet project begun in the same year he got married, 1475, seals the altarpiece, too, as one of his projects, and gives us the name of

one of the commissioners. The sea that can be seen in the medal for Costanzo's Castle is still very close to the Rocca Costanza in Pesaro today:

Two guardian saints framing stories of suffering in the predella, with a reminder of death, a memento mori, high above the altarpiece in the gable.

They punctuate in the center the concern for death and suffering of the rest of the altar.

And yet what Bellini puts in the center with the largest figures is the happy story of the Coronation.

And the beautiful Venetian light he throws on the scene from the left so that it lights up the golden

orb on Christ's gown tells us that he is, ultimately, an optimist. Worth a trip to Pesaro to be reminded

of life's glories.

No comments:

Post a Comment