Fra Angelico's large Annunciation fresco painted between 1435 and 1445 for the convent of San Marco in Florence is a great example of why it is important to look at the context in which art works are produced in order to understand them. (Best book on the monastery decoration is William Hood, Fra Angelico at San Marco, Yale Press, 1993.)

This painting is a large fresco painted on the wall of a Dominican monastery dedicated to Saint Mark in the city of Florence. The scene represented is the Angel Gabriel coming to tell the Virgin Mary that she will be impregnated by God and bear the Messiah. The fresco appears at the top of the stairs which run from the refectory to the living quarters in San Marco.

A Dominican monk himself, Fra Angelico wanted to make an image of Mary that reflected the simple life of the monks who lived in cells on the second floor of the monastery.

The stool in the painting looks like a simple wooden stool,

the walls of the Virgin's house are not decorated, and she wears simple clothing and no jewellery. The cell room with one window depicted behind her resembles the cells with one window in the monastery itself, right down the hallway on either side of the painting.

The fictive Corinthian capitals in the foreground of the painting look like the actual Corinthian capitals designed by Michelozzo for plain columns holding up the courtyard of the Medici Palace on Via Larga (Via Cavour.)

And the fictive Ionic capitals with the plain, unfluted columns which fence in the space of her room on the left are identical to the actual Ionic capitals and columns in the library just down the monastery hall to the right of the image.

It is still a library designed by Michelozzo that contains displays of wonderful 15th-century manuscripts. The library collection was either paid for by Cosimo de' Medici or came from the private library of Cosimo's close friend, Niccolo Niccoli. When Niccoli died, Cosimo took over his

library and with it began the monastery library, then added his own purchases afterwards.

To see how the Annunciation fits in to the lives of the monks living in the cells, it is a good idea

to look at a plan of the monastery on the second floor:

The church is on the left, the courtyard with the monks' cells on the right, the library at D. At the top of the stairs from the first floor, at small @ at the back of the plan is the Annunciation on the hallway wall. At 38 to the left of @ further down the hallway is a room with a stairwell next to it that leads to the church. That room and the room behind it, 39, were private cells of the patron of the monastery, Cosimo de' Medici, the de facto leader of Florence in the period Fra Angelico is painting, 1435-45. Originally, not shown on this map, there was a connecting corridor from Cosimo de' Medici's two cells to the library as well. The route from his second cell to the library is shown below in yellow:

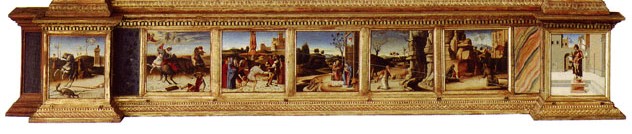

The stairs to the church and the corridor to the library intimate that Cosimo could come and go without interacting with the monks at all. Cosimo was so invested in the monastery that he gave money for the main altarpiece for the church, painted by Fra Angelico:

directly from the church nave up to the condo he set up for Cosimo. Cosimo, the great Florentine banker and businessman, would come to San Marco for meditation and prayer and reading, and to get away from his family home down the street on Via Larga (now Via Cavour).

Since Cosimo was a member of the Confraternity of the Magi and probably participated in great pageant parades in June for the celebration of the Feast of the Magi (January 6th being too cold for parades,) the painting of the story of the Magi in his private layman's cell was self-reflective and congratulatory. He did not become a monk, he lived as a layman, but because he paid for the monastic community's building and church, as well as Fra Angelico's salary as painter of the cells and altarpiece, he was given special privileges and allowed to visit his monastic lodgings whenever he wished. From there he could access the library to look at his manuscripts, too.

But what does he have to do with the Annunciation painted at the top of the stairs? He was the

patron who paid for it, too, but for its decoration he was not thinking about himself; he would have been thinking about the welfare of the monks who lived in the cells.

They dedicated their lives to Mary, so an image of the Virgin at the beginning of her motherhood would have stimulated them to be as humble and submissive as she was when approached by the angel. The fact that Fra Angelico's Annunciation is painted in the ACCEPTANCE STAGE is in keeping with how Cosimo and the church superiors would have wanted the monks to view their own lives, as lives accepting God's will in the same way that Mary did. Her simple surroundings reinforce their own servitude and plain living and would help them to agree to exclusion from life outside the monastery and to adhere to the purpose of a simple, clean, good existence.

The green bushes and dark green cypresses (symbols of death) seen beyond the wooden fence enclosure on the left of the painting are at once a reference to the Garden of Eden where original sin began and a reference to the fact that later Christ will die for everyone's sins and atone for the Garden of Eden. Within the enclosure there is a green lawn with flowers springing up. That is meant to be a visual depiction of Mary as the "hortus conclusus" the "enclosed garden" and the "porta clausa," the

"closed door," both of which were terms applied to her in her mysterious capacity to be a virgin and fertile at the same time.

On the bottom pavement of the Annunciation scene are written two things in Latin. The first says,

"Salve,

Mater pietatis / et totius Trinitatis / nobile triclinium / Maria!"

Hail, Mother of mercy and the

complete Trinity, noble resting place, Mary!

and another which says, "Beware, lest you fail to say

a Hail Mary when passing by this image of the intact Virgin."

The first is addressed to the Virgin in praise of her. The second seems to be an admonitory regulation

of the monks who would pass by this image on their way to meals and church services several times a day. Their prayers were required when going up and down the stairs.

The stair Annunciation painted by Fra Angelico sometime between 1435 and 1445 served then as

a focal image for the comings and goings of the monks living there. The light source in the painting comes from the left, and in the hallway there is a window to the left of the painting, so the real light and the pictorial light combine to make the image look realistic. The shadows of the Virgin's body fall to the right, suggesting the light is coming from the left. The arches are lit on the exterior or right,

suggesting left-streaming light. The space is set up using not quite perfect one-point perspective, but the diagonals meet within the lighted window of the small cell, by which the artist is saying that the center of their universe is light. Angelico's light and architecture create the illusion that the room of the Virgin and Angel continues beyond the wall as one walks up the stairs, as though he has made another cell without real building materials, mirroring the magical transformation in the scene of the Virgin into mother.

One of my friends reports that the last step of this flight of stairs up to the fresco is higher than the other steps, with the result that anyone coming up these stairs into the monastic living quarters, is forced to their knees by the physical encumbrance of the stair height. Exactly what the monk's superiors wanted; a submissive and praying friar, ready to say Hail Mary to the woman who received a message from an unearthly being with acceptance. And the acceptance extends to an angel whose wings are in an unlikely rainbow pattern:

Gabriel's wings become a symbol of all that is luminescent and miraculous about this event. The monks would have understood that their attraction to the beauty of these wings could ensure their

acceptance of the lives of prayer and fasting, to some, lives of physical hardship. Fra Angelico created a beautiful scene to enhance the religious fervor of his fellow cell-mates. Cosimo paid for the work but his own stairs from the nave had no such image. Cosimo could return to his palazzo and the real world after his time of meditation in his own cells. For the Dominicans in the confines of the monastery, no such relief. But both Cosimo and Fra Angelico realized that they could offer the monks a divine consolation. How much easier it was to enter into the rigor of monastic deprivation if your visual senses could be stimulated and caressed with two sweet beings encountering love.

The Annunciation fresco of Fra Angelico offered private joy at the top of the stair, an intimacy that

made all hardship bearable.

Between FEAR AND REFLECTION:

Between FEAR AND REFLECTION: