Masaccio's TRIBUTE MONEY and ADAM AND EVE

in the Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine (1424-27), Florence

The story of the Tribute Money can be found in Matthew 17: 24-27 in the New Testament:

"And when they were come to Capernaum, they that received tribute money came to Peter and said, 'Doth not your master pay tribute?' He saith, ' Yes.' And when he was come into the house, Jesus prevented him, saying, 'What thinkest thou, Simon? of whom do the kings of the earth take custom or tribute? of their own children, or of strangers?' Peter saith unto him, 'of strangers.' Jesus saith unto him, 'Then are the children free. Notwithstanding, lest we should offend them, go thou to the sea, and cast an hook, and take up the fish that first cometh up; and when thou hast opened his mouth, thou shalt find a piece of money; that take, and give unto them for me and thee.'"

Masaccio's version of the tale is on the second tier of the left wall of the Brancacci Chapel in the Carmelite church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence.

From the text he includes a set of stairs with a wall at the far right of the scene, which imply the toll border gate for the city of Capernaum. The tax collector in Masaccio's version wears a 15th-century red tunic, while St. Peter and all the other disciples wear ancient long robes.

From the text he includes a set of stairs with a wall at the far right of the scene, which imply the toll border gate for the city of Capernaum. The tax collector in Masaccio's version wears a 15th-century red tunic, while St. Peter and all the other disciples wear ancient long robes.

Masaccio's version also sets at the right the house mentioned in the text. Everyone stands outside the house, especially the tax collector, who in the text is prevented from entering the house.

The tax collector appears twice in the scene, once to ask Christ for money, then on the right to receive the money from St. Peter.

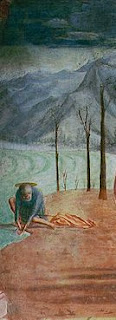

The discussion about taxation is depicted in the center while the act of Peter getting money from the mouth of the fish is on the far left; in fact, Peter appears three times, left, center, and right, in a blue undergarment and yellow outer robe:

Christ appears once in this painted version; he is the compositional and dramatic center of the group of

Although the more delicate head of Christ may be by Masaccio's companion painter in the chapel, Masolino,

the composition, the weighty figures, the landscape background, and the serious demeanor of everyone in the scene are consistent with Masaccio's style.

Before discussing the relation between this painting and the Expulsion painted to the left of it, it is important to note three things:

1. The repetition of Peter and the tax collector suggests that the painting is still conceived in a Gothic mode where there is no unity of time and space, and narrative and emotion are the main concerns. The other Gothic element is the large size of the figures in relation to the architecture. So, although Masaccio is the first painter to use one-point perspective in a wall painting in Western art history, an innovation we associate with Renaissance thinking, he retains vestiges of the Gothic tradition at the same time that he exhibits revolutionary ways of portraying space.

2. The hand gestures in the painting are aligned all in a horizontal rectangle so that the reader of the painting can quickly and easily "read" the stages of the narrative:

The tax collector points to the gate with his right hand and holds out his left palm for money from Christ. Christ holds his blue robe with his left hand and gestures with his right to Peter and to the fish in the lake. Peter repeats Christ's gesture towards the lake with his right hand. Peter's hands fall within the same rectangle where he opens the mouth of the fish to retrieve the coin. The tax collector's back forces the viewer to look at the hands and follow the tax collector's right hand over to the scene where Peter pays him with right hand in right hand.

The tax collector points to the gate with his right hand and holds out his left palm for money from Christ. Christ holds his blue robe with his left hand and gestures with his right to Peter and to the fish in the lake. Peter repeats Christ's gesture towards the lake with his right hand. Peter's hands fall within the same rectangle where he opens the mouth of the fish to retrieve the coin. The tax collector's back forces the viewer to look at the hands and follow the tax collector's right hand over to the scene where Peter pays him with right hand in right hand.

The hand gestures lead the viewer through the story and the painted spaces, indicating the sequences from demand of payment to finding payment to final payment.

3. The new and Renaissance elements in Masaccio's Tribute Money are not limited to the one-point perspective. Peter's crouching body at the lake shows Masaccio's interest in foreshortening in Peter's face, his right knee, and his left foot. His interest in using classical statues for models for the figures is clear in his tax collector who is drawn, literally, from an ancient Roman statue of Antinous:

Masaccio takes the right arm gesture of the ancient Roman figure, the bent knee with weight on the right leg, and the bent left arm, as well as the angle of the head in relation to the torso.

He clothes the figure, gives him straighter hair, and extends the right palm out to present him as collecting Peter's coin, but he has made the tax collector's body look as though it responds to gravity as the heavy marble statue would. We see the accurate display of anatomy in the body of the tax-collector that is present in the statue of Antinous. While the tax collector is the only one in the scene wearing Florentine contemporary dress, a way of implying that paying taxes even in 1427 in Florence is a good thing (supporting the catasto implemented in the city in 1427), the use of the ancient statue as the model for the figure casts a serious and ancient history behind him.

The consistent light source that Masaccio exhibits on both tiers of this wall of the chapel is another Renaissance element that makes his painting stand out from Gothic precedents. The shadows cast by the figures all fall to the left of the people. The actual light source in the chapel is the window at the back of the chapel, so that the natural light would cast shadows exactly where he has painted them, from the right falling to the left. The result is that, in spite of the disunity of time and space in repeating people in the narrative, the light source unites them back together. The shadows of both Peter and the tax collector fall to the left of their bodies:

The shadows of the disciples and the tax collector seen from the back also fall to the left:The shadows of Peter's leg and left arm fall to the left, even into the lake:

As if that weren't enough gluing of the narrative scenes into a cohesive whole, Masaccio's concern for a complete and universal message continues in two other ways:

1. the background landscape of mountains and sky encircle the scene as a whole,

1. the background landscape of mountains and sky encircle the scene as a whole,

even peeking out behind the wall of the house on the right side of the painting.

2. Masaccio encloses the space of Peter's story at right and left sides with two similar pilasters that have pink capitals and pink bases:

While these pilasters are meant to form the frames of the story of the Tribute Money and contain that story as separate from the earlier Genesis story, they actually allow the viewer to connect the New Testament story with the Old Testament story to the left of them: the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise:

,_Masaccio.jpg)

The gate looks like a modern abstraction of a gate at first, but when you look at 14th-century Florentine gates, such as Porta San Niccolo (crenellations added in 19th-century but in keeping with Gothic examples), it is clear that Masaccio wants to associate Adam and Eve's expulsion with one of the worst punishments in the15th century, exile from the city.

Adam and Eve are pushed out of the Garden of Eden and are exiled from God's favor and love. They are sent out of a city gate to face desperation, a desperation that exile from Florence would have been for a 15th-century viewer.

They walk out of step with each other and out of step with their origins in the Garden.

Adam steps forward with his left foot and draws his right foot off the threshold of the gate. Eve steps forward with her right foot and draws her left foot up; they do not walk in harmony with each other: their steps are out of sync and neither one of them acknowledges the other. They are absorbed in the painful feelings they experience for the first time as they are pushed out of Paradise. They are in disharmony not just with each other but with God. Their footsteps, therefore, represent their being "out of step" with the deity. The Bible says that they will be punished in different ways for having disobeyed God and eaten of the Tree of Knowledge.

But those punishments are not the primary reason they are weeping. They are weeping because they know that outside the Garden they will have to die. In Eden they lived eternal life. In exile they will know death.

How can the problem presented by Original Sin in the Old Testament be given a solution in the New?

How does Masaccio solve the problem of connecting these two seemingly separate stories? The answer to both questions lies in Adam's genitals.

They are prominent and realistically rendered by Masaccio. Adam is not circumcised. It may be that Masaccio knew that Adam was not circumcised, as that rite is instituted first by Abraham, 19 generations after Adam and Eve (Genesis 17:10-14). But as a 15th-century Christian man, Masaccio would have most familiar, presumably, with the anatomy of non-circumcised males, and he paints what he knows.Adam and Eve have only one hope left to them in the despair of their exile. They can be saved by one of their offspring. Christ's Resurrection is the answer to the question of death for Christian believers.

In Masaccio's presentation of the two stories Christ points with his right hand in Peter's direction, but when we view the two scenes together, Christ looks at Adam and Eve and points to them. He is giving Peter a way to look for the tax money, but he is also offering a "payment" to Adam and Eve for their sins.

Adam and Eve walk out of the gate of the Garden, but they also walk towards Christ in the next scene. The natural light that produces shadows to the left of Christ and the disciples also produces shadows that fall to the left of Adam and Eve. The consistent light source for both scenes conflates the historical differences in time. Adam and Eve's sins are given a reassuring welcoming arm in the Tribute Money, their nakedness a reassuring covering of cloth in the heavy drapery worn by Christ and his disciples.

But how can Adam and Eve be rescued by reproducing? They walk forward together without knowing that their salvation lies in the future, but they walk forward, toward Christ. Christ is not the product of their immediate union, but he is one of their offspring, related to them through genes. How can that be if Joseph is of the lineage of Adam and Eve and Joseph is not Christ's father? Christ is not connected to them through Joseph; he is one of their relatives through his mother because Mary was of the lineage of David, who could trace his family history back to Adam and Eve.

So the prominence of Adam's genitals in the Expulsion scene is directly relevant to the Tribute Money gestures. Christ is looking back toward his ancestors, back through history. His purpose on earth is to pay for Adam and Eve's sins with his own life. Christ's Crucifixion, his real payment as opposed to the coin paid by Peter, is not painted by Masaccio or Masolino in the chapel partly because the fresco cycle is Petrine, that is, just stories about St. Peter. But in the Tribute Money scene Masaccio does not give the one-point of the perspective to Peter; he gives the central place to Christ.

Christ is the only descendant of Adam and Eve who can offer to human beings a path out of the anguish caused by the thought of death. Masaccio's way of conveying that exquisite promise is to show the viewer the power of male reproductive potential, a surge worthy of a resurrected life.

No comments:

Post a Comment