The influence of Brunelleschi's invention of one-point perspective can be seen clearly in Masaccio's fresco of 1424-27 in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, the Tribute Money:

All the diagonal lines in the painting come to a point at Christ's head; the center of the composition is directed toward the center of the drama, the main protagonist. This technique is demonstrated many years before, in two panel paintings by Brunelleschi himself, but those panels are now lost. Masaccio's Tribute Money is thus the first fresco painting in Western history to use one-point-perspective. In sculpture Donatello plays with Brunelleschi's one-point perspective in his bas-relief for his St. George on Orsanmichele, but his lines just vaguely suggest a center point near George's head:

Donatello seems willing to admit that Brunelleschi has a good idea for creating realistic space, but he is more interested in the emotional relation between the Princess on the right and her rescuer, the saint on horseback who is killing the dragon for her, than he is in the exact arrival of the diagonals in one point.

Brunelleschi's ideas about perspective emerge probably as early as 1409; that year is the date given in a story (Il Grasso Legnaiuolo - The Fat Carpenter) about Brunelleschi in which he manipulates the space of one of his friends to make his friend think he has turned into someone else. The magical transformation Brunelleschi engineers in that story has many parallels to his manipulation of space in the technique of one-point perspective.

My chronology, then, for the use of one-point perspective in Italian art:

1409 - Invention of one-point perspective; Brunelleschi's panels (Baptistery and Palazzo Vecchio)

1417 - Donatello's St. George bas-relief (not perfect but experimenting with it in sculpture)

1424-27 - Masaccio's Tribute Money (perfect one-point perspective in fresco; the space created still contains people too large for the buildings)

1438-45 - Fra Angelico's San Marco altarpiece (first large-scale altarpiece using one-point perspective where the people fit proportionally into the space):

But what about the period between Masaccio's fresco and Fra Angelico's panel? What happens to Brunelleschi's ideas for perspective in the ten years after Masaccio's death in 1428?

The answer lies not in painting, not in sculpture, but in a Renaissance art form that is less familiar to most viewers: INTARSIA, wood inlay.

Margaret Haines has written a wonderful book about the largest project of wood inlay in Florence during this period: THE SACRESTIA DELLE MESSE of the FLORENTINE CATHEDRAL (Florence, Cassa di Risparmio, 1983) in which she presents the room of the North Sacristy (the Sacristy of the Masses) and lays out the 15th-century documents for the decoration of these walls entirely in wood inlay.

According to Haines, the earliest intarsia in the room is on the left (north) wall and made by a friend/rival of Brunelleschi's, Antonio Manetti Ciaccheri (not to be confused with Brunelleschi's biographer, Antonio di Tuccio Manetti). Manetti Ciaccheri was a woodworker and architectural designer who competed with Brunelleschi for the lantern of the Cathedral dome in Florence. Haines shows that in the same year that Brunelleschi wins that competition, 1436, Manetti is named in the documents as the worker carrying out the North left wall in the North Sacristy. Manetti has helpers, but in later documents he is the main "conductori unius lateris prime sacrestie."(Haines, pp.72-73) It is unclear if he did the original designs for the North wall, but his execution is superb. His inlay work begun in 1436 is probably completed by 1445. It is the first and most remarkable statement about one-point perspective in wood inlay.

The sacristy is in the left door behind the altar in Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence (not always open to the public but sometimes viewable):

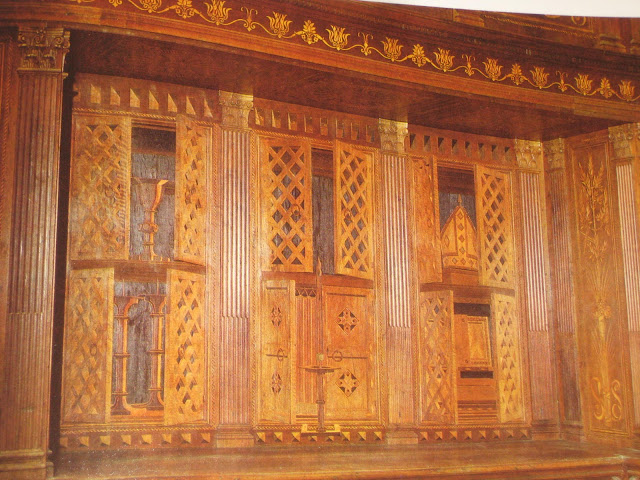

Set back from the real drawers on every wall are panels of wood inlay that appear to open up areas of depth and space. The earliest section begun in 1436 is the indented section of the left wall:

Three feet in from the drawers there appear to be six cabinets with doors ajar and objects on the shelves behind the doors. In the right upper cabinet is a bishop's miter (since Florence was a bishopric there would have been vestments and miters for the bishop in the sacristy):

The miter rests on a box and in the cabinet below appears a lectern:

In the upper far left cabinet is a chalice to hold the wine celebrated in the mass:and in the cabinet below the chalice, two candlesticks ready for carrying to the altar but without candles.

The doors of five of the cabinets appear to be made of see-through latticework with real round iron handles. They appear to be deliberately set ajar so that we see the objects on the shelves. What is amazing about all of the inlay on this wall is that all of it is illusion: if you run your hand over the surface of the woodwork, it is completely flat because all of the variously colored pieces of wood are set into one frame. The cabinet doors that seem to project out are just actually flat. And all of the objects which seem to be metal, the round handles and hinges, all are made of wood.

Antonio Manetti makes it seem as though the doors of the cabinets are coming towards the viewer, and that we could pick up the objects on the shelves, but in reality, it is entirely an optical illusion and the wood surface has no doors ajar, no objects, and no actual lattice-work.

Using spindle wood for the white areas, bog oak for the dark, and combining various other woods such as pear and cherry, he gives the viewer the sensation that they stand in front of doors with hinges and see-through sections and that if they reach to pull on the faux-metal round handles, they can swing the door in or out. The bottom parts of the doors seem to hang over the edges of the shelves and into the viewer's space. Using one-point perspective Manetti creates a tour de force in wood inlay to convince the viewer they are in the presence of fairly deep space and real closets. The only actual raised elements in the wall surface here are the fluted pilasters set between the cabinets and the actual drawers set forward from the wall below the cabinets. The rest is flat surface and bold illusion constructed using one-point perspective.

While the two side cabinets hold objects that might actually be used in a mass, i.e., the bishop's miter, the bookstand, the chalice, and the candlesticks, the central cabinet is Manetti's piece de resistance. The upper cabinet doors are ajar but there is nothing but darkness on the shelf behind them.

Reaching into the darkness from below is the flame of a lit candle set on a hexagonal pedestal that rests on a square base that appears to project from the wall in front of the lower cabinet. The central lower cabinet is not made of latticework and one of the doors is closed. A fictive curtain with fringe is drawn across the opening and the closed door has a key-hole.

The lit candle, the curtain, and the door with a lock all suggest a tabernacle for the bread or wafer used in the mass. Since in Catholic masses the bread becomes the body of Christ to be fed to the congregation and since that transformation is considered one of the great mysteries of Catholic faith, the bread used in Masses is usually (even now) kept in locked containers in sacristies to protect it. A curtain is drawn over its resting place and a lit candle placed in front of it to honor Christ. That a sacristy would need a tabernacle for holding the bread of the mass celebration is a norm understood by Catholic priests and congregants alike.

During the period that this wall is created (1436-1445), the Florence Cathedral's dome was incomplete and open to the sky. Mass was not said at the central altar until the lantern was constructed to cover the hole in the dome between 1446-69, but it would have been possible to say mass at the main altar under a covered roof by 1461. When Antonio Manetti begins his tabernacle, the Cathedral dome would have looked much like the oculus of the Pantheon in Rome, an open hole

:

:

Masses in the Cathedral in 1436 were said in side chapels where participants could gather without worry about weather. Antonio Manetti understood the anxiety about the tabernacle needed for Catholic faith to continue in a large church where the building is still under construction. He creates, using one-point perspective wood inlay, a permanent tabernacle with a candle lit in front of the central mystery of the mass. The light from that candle plays over the surfaces of the cabinets and objects adjacent to its shrine.

During Manetti's era and even now Christ is known as the "light of the world." The presence of light is implied on all of the objects in the cupboards on both sides of the candle. The faux light of the candle pierces the darkness above the tabernacle where the "body of Christ" is housed. Manetti's trompe l'oeil chalices, candlesticks, miter, curtain, and bookstand are all touched by the eternal light of his wood flame. His illusion extends even behind the curtain of the tabernacle.

No comments:

Post a Comment