Up to now most scholars have described the altarpiece which Giovanni Bellini painted in 1505 for the convent church of San Zaccaria in Venice as an image of the Madonna and Child with saints Peter, Catherine, Lucy, and Jerome.

St. Peter is easy to identify on the far left because he carries keys as well as a book. Catherine, too, holds the palm of martyrdom in her right hand and touches the wheel of her martyrdom with her left.

Lucy is occasionally mistaken in the descriptions for Mary Magdalene,

but the martyr's palm in her left hand rules out Mary Magdalene. And

although both Lucy and Magdalene often hold oil lamps, the oil in this

lamp has traces of the eyes which, according to legend, Lucy had gouged

out to demonstrate her devotion to virginity and the Virgin and to

dissuade her boyfriend who admired them. The Virgin later restored her

eyesight, so the nearly blond girl with eyes looking down at her

previous eyes, is Lucia, (light), St. Lucy.

That leaves the far right male figure clad in a red mantle with white underlining, who looks down at an open book he is holding with both hands; the hands seem to have gloves on them and the undergarment sleeves are embroidered. The only identification for this figure that I have seen in print is Saint Jerome, but I don't believe it is Jerome.

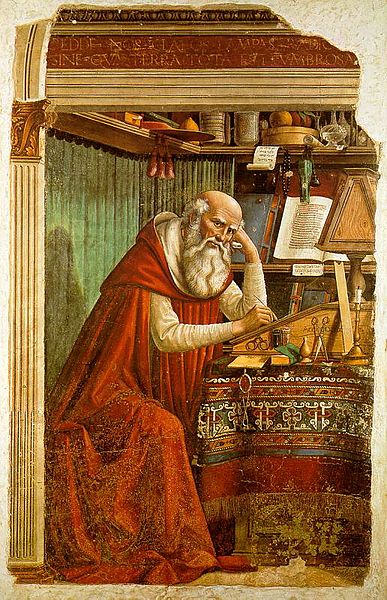

It is understandable why St. Jerome first comes to mind when looking at this male saint. Jerome is depicted usually in three different ways in Renaissance images.

1. Jerome as Cardinal: Often he is dressed in a red cardinal's cape and his red cardinal hat is prominently displayed somewhere near him, as in this Ognissanti fresco in Florence of St. Jerome in his Study by Ghirlandaio of 1480, where the tassels of the hat dangle from the shelf above him:

or this Antonello da Messina example in the London National Gallery (1460) where the cardinal hat lies on the bench behind him:

2. Jerome as Church Father: Sometimes Jerome is painted with cardinal hat on and holding a church model. He is a model for the church as he is considered a church father. Two examples of this type of Jerome in Venice are:

Vivarini's altarpiece of the 1440's for the Santa Sabina chapel in the same church where Bellini painted, San Zaccaria:

or Bellini's father, Iacopo Bellini's altarpiece of 1460-64 for the Carita in Venice where Jerome stands on left holding church.

3. Jerome as ascetic monk:The third type of Jerome is that of the ascetic monk living in the desert, sometimes with his lion:

Three examples of this type by Bellini himself, from the Uffizi, S. Crisostomo, Venice, and Ashmolean respectively:

Uffizi

S. Crisostomo, 1513 Ashmolean

But the red-clad saint in Bellini's San Zaccaria altarpiece has no red cardinal hat, no church model, is not dressed as an ascetic monk, and certainly has no lion. He is none of the usual types associated with Jerome. So is this Saint Jerome at all? And if not, then, who is he?

To answer that question we must look at the setting for Bellini's 1505 altarpiece, the church of San Zaccaria. The name of the church is derived from the major relic contained within it, the

body of Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist.

Because of the holy relation of John and Jesus, Zacharias is made a saint in Venice, San Zaccaria in Italian. The nuns of the

convent received the body of St. Zacharias from the Byzantine Emperor

Leo V in the 9th century and the new Renaissance church (1490-1504) designed by Gambello and then

Mauro Codussi was built to house the relic.

So the church is dedicated to Zacharias on the outside; and inside, the decoration also pays attention to him. The first thing one encounters when entering the church is the baptismal font. The statue in the middle of that fountain is another statue of Zacharias of 1543 by Alessandro Vittoria (photo by Giovanni dall'Orto):

The Vittoria statues inside and out are later than Bellini's altarpiece, but they give us some idea of how Zacharias was conceived by Renaissance artists: here he is a New Testament prophet, priest of the temple, dressed in long flowing robes which are draped over his head, and in his left hand he holds a book, presumably anachronistically, the Bible, or perhaps, as we shall see later, the book in which he writes his son's name.

The next thing one notices in the nave of the church is the wall decoration on either side of the nave.The mural decoration for the nave was divided between the Virgin, whose stories are told on the left nave walls and Saint Zacharias and his son, John the Baptist, both of whose stories are told on the right walls of the nave.

Then one becomes aware of two protrusions from the side walls of the nave, both in the second chapel; on the right, the tomb of Zacharias:

And just opposite it, Bellini's altarpiece, in the second chapel on the left:

Bellini would have known that his wall painting was meant to fit into the stories of the Virgin, hence his altarpiece was a sacra conversazione, a sacred conversation of the Virgin and Child with saints in the same space. But he must have also been conscious of the position of his altar with respect to the tomb of Zacharias, the name saint of the church itself. Since he includes Peter in deference to the patron, whose name was Peter (Pietro Cappello), why should he not place the name saint of the church in the place of honor closest to the main altar, the saint whose relic was housed just opposite, namely Saint Zacharias? And what better way to honor the name saint of the church buried just opposite than with a painted image of him facing his tomb?

What about Zacharias makes him appropriate to be placed within the sacred space of the Madonna and Child Enthroned? Zacharias' story is told in Luke 1, 5-25 and then gets expanded in the life of the Virgin in the Golden Legend. Zacharias is the father of John the Baptist and was himself assistant

priest in the temple. He is married to Elizabeth, Mary's cousin, and he

helps to officiate at the Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple.(See David Rosand on Titian's Presentation in the Temple of 1534.) He

also figures in the fresco cycles about his son's life because his son's

birth was considered a miracle. Zacharias and Elizabeth were both old

people and had wanted to have children but were barren. He offers incense in

the temple one day, whereupon an angel appears and tells him he

will have a child. As a sign of God's power in the birth, the angel says Zacharias will be struck mute for some time so that everyone will

understand that he has been visited by God and that the birth is miraculous. John is born and people

assume the baby will be called Zacharias after his father. Elizabeth says

that he will be called John and people question her decision and go to

ask Zacharias, who still can't talk. The moment he writes down his son's

name, John, he regains speech. God's intervention in his life is marked by his being struck mute.And just opposite it, Bellini's altarpiece, in the second chapel on the left:

Bellini would have known that his wall painting was meant to fit into the stories of the Virgin, hence his altarpiece was a sacra conversazione, a sacred conversation of the Virgin and Child with saints in the same space. But he must have also been conscious of the position of his altar with respect to the tomb of Zacharias, the name saint of the church itself. Since he includes Peter in deference to the patron, whose name was Peter (Pietro Cappello), why should he not place the name saint of the church in the place of honor closest to the main altar, the saint whose relic was housed just opposite, namely Saint Zacharias? And what better way to honor the name saint of the church buried just opposite than with a painted image of him facing his tomb?

In order to confirm that Bellini's red-clad saint is Zacharias, we need to look at colored images of Zacharias before Bellini's. Between 1485-90 Ghirlandaio paints the story of Zacharias in his fresco cycle about the life of John the Baptist for Giovanni Tornabuoni in Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The first image of the cycle is of Zacharias, in red robe with white underlining, being visited by the angel Gabriel at the temple altar:

Ghirlandaio's

idea of Zacharias as priest includes an undergarment that is

embroidered and his mantle has a hood. Zacharias is a white-haired,

white-bearded man with white mustache. Zacharias is painted again in the same cycle when he decides to write down his son's name:

Again he is a white-bearded old man with red cloak seated in the center of the group (his undergarment is green, the only difference from the image in Bellini):

Again he is a white-bearded old man with red cloak seated in the center of the group (his undergarment is green, the only difference from the image in Bellini):

In the Zaccaria altarpiece, the

male figure in red on the right faces frontally, has a long white beard

and wears a red cloak in much the same way he does in the earlier

Florentine fresco. Bellini has made nearly all of the figures in this

altarpiece look

down, not at each other, not at the Madonna and not at the viewer. The Madonna and Child look down as well.

Even the bas-relief of God the father over the throne does not look out, is silent as stone.

The only person who could be thought to be looking out is the musician who glances toward the entrance to the church. But the musician perhaps has stopped playing, is listening,

so the effect is an atmosphere of silence and contemplation. It is the silence that Bellini wishes to infuse in his painting to remind the viewer of God's stopping the voice of Zacharias, God's turning Zacharias mute. Zacharias looks down with mouth closed. He holds his book without speaking; he is mute. He contemplates the word of God in the book that is so precious he wears gloves so as not to defile it. The gloves muffle the sound of the hands on the book. God's will silenced Zacharias' life and the power of that silence is present in the world of this altarpiece. The sacred conversation here is a sacred place of no conversation. No sound and no movement. The four saints are caught in the silent power of God's plan in their lives. The figures force the viewer to stillness, too, in front of the altarpiece; they force the viewers to think silently about the mystery of God in their own lives. Behind Zacharias to the right are two trees, one barren and one in leaf, that echo in visual clues the change in Zacharias' body from one that was barren to one that conceived life.

The red-cloaked priest of the temple here is Zacharias, in the temple of San Zaccaria, where his body lies directly across from his painted image. Bellini understood that Zacharias was a relative of Mary; his wife was Mary's cousin, and both his wife and Mary conceived children miraculously. Zacharias' own belief in the power of God in his own life is conveyed through his still contemplation of the word of God in the book he is holding. He has known Mary as a small child and now he stands with her in a space where she holds her own small child on her lap. He knows his own child, John the Baptist, is the prophet who will tell the world of Christ before Christ is revealed. As a priest of the temple, his job is to interpret the word of God, and in this image, he is deeply engrossed in the book of that word. The same angel who visits Mary, Gabriel, visits Zacharias, to tell him of God's power. Gabriel says to Zacharias,"And behold, thou shalt be dumb, and not able to speak, until the day that these things shall be performed, because thou believed not my words, which shall be fulfilled in their season." Zacharias in Bellini's work believes the words now because he has already had a son five months before Mary's in the altarpiece. He contemplates the space and time of his own life laid out between Bellini's painting and the tomb across from it, a lifetime in which the power of silence and prayer has given him hope, and the wisdom to remain quiet in the face of miracles.

Should we need further confirmation that this man is Zacharias, we need only look at an earlier painted image of Zacharias in the same church. In 1442 Andrea del Castagno paints the ceiling of the nun's Chapel of San Tarasio, further along and to the right of the nave in the church of San Zaccaria: the very far right figure in his ceiling fresco appears opposite St. John the Baptist who is on the far left; the furthest right saint there is a figure clad in red robe with white underlining who stands on the ceiling along with God the father and the four Evangelists.The red hood wraps over the top of his head. He is the name saint of the church, John's father, Zacharias:

If Bellini had any doubts about how to depict Zacharias in his altarpiece, he had only to walk down the church hall.

Castagno's image has been forgotten over the centuries, but Bellini's still brings in the noisy crowds, and suddenly, before the beauty of Bellini's art, they are struck mute.

But wait, what is that hovering over Bellini's altar? Is it an incense burner?

(For more on the church see Gary M. Radke's illuminating article “Nuns and Their Art: The Case of San Zaccaria in Renaissance Venice.” Renaissance Quarterly 54 (2001 ): 430-59.)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment