MONET's GIVERNY

Once Claude Monet (1840-1926) had made enough money from his paintings to buy property, he moved with his family to a large house in Giverny west of Paris near the River Epte. There, beginning in the 1890's, he had two gardens planted, a formal flower garden with regular paths behind the house (upper section in plan), and a second water garden further from the house with bridge, weeping willows, and water lilies (lower section in plan, photo right with wisteria on the bridge.)

House

Photo and painting of formal garden:

Photo and painting of second, water garden (painted bridge has been replaced with a lower arc bridge now):

Photo and painting of second, water garden (painted bridge has been replaced with a lower arc bridge now):

The Epte River (a tributary of the Seine) was and is the source of the water for the second garden. From 1890 to the end of his life Monet painted that water garden in some of the most memorable images of nature's beauty.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y., 1899 Washington, National Gallery of Art, 1899

Princeton Univ. Art Gallery, 1897-99

Water Lilies, 1906, Art Institute of Chicago

The paintings that he did there of the Japanese bridge and the water lilies beneath it sum up 3 themes which interested Monet throughout his life:

1) LIGHT on the surface of WATER and BUILDINGS

2) FLOWERS

3) SERIES OF THE SAME SCENE repeated at different times of day.

1) LIGHT on the SURFACE OF WATER and BUILDINGS is something that captivated him from the beginning. In fact, the very first painting exhibited that is connected directly with the term "IMPRESSIONISM" was his 1872 painting of the harbor at Le Havre where light, water, and buildings appear. In the scene we see boats and figures sketched in silhouettes against the main subject, the sun's reflection on the water in the harbor at sunrise. The title of this work in French, Impression: Soleil Levant, (Impression: Sunrise) is what caused critics of the painting to coin the phrase "IMPRESSIONISM" which was then applied to art works made by Monet and others.

It is such an "impression" that the viewer cannot distinguish which vertical black or blue strokes represent smokestacks and which represent trees or ships' masts; they look very much alike. The thickest paint strokes are horizontal, visible, and irregular, much like the sun's rays would be on various surfaces: orange and yellow for the light bouncing off the moving water, dark green strokes for the water waves and for the reflections of the figure and boat to the left of the sun's reflection. The people are less important than the single orange globe in the middle of the sky. Impasto orange and gold stripes raised like embossed gold leaf sections on the surface of the painting form a thick path for the viewer to follow into the distance to the center of the perspective.

Nature, in the shape of a perfect circle, is the focus of the scene, but Monet keeps human connection to the sun by illuminating the human figures as parts of the shadows cast by the star's light. The artist does not care if the viewer sees his brushstrokes; he is saying, "I want to capture the light and color I seem to see, the movement of the water, and the mood established at sunrise on the harbor." Nature overshadows humans, literally. The LIGHT on the SURFACE of the WATER is what hooks the artist and viewer. Life is just about to stir in the harbor; the fishing boats are heading out to sea, the cranes are about to move, the smokestacks are piping up, the sails of the sailing ships have yet to be hoisted up the masts. But the scene could almost equally be a scene of the sunset in the same place; the time of day is subservient to the observation of light from the sun through clouds.

In his later Giverny works, LIGHT on the SURFACE of WATER and BUILDINGS is also the real subject of the art:

The viewer sometimes wonders if the water surface in the painting is cloud and sky reflected or water itself. The light picks out the green of the lily pads, the pink of the lilies, the whites of the clouds, or is it mist?(On a side note the mist painting sold in July 2014 for 31 million dollars at Sotheby's.) Sometimes the objects seem an excuse for a colorful rendering of light itself. Even the man-made bridge in the scene is transformed into an arc of light and color where the viewer is more aware of the shimmering on the bridge panels than of their actual structure:

Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge, 1897-99, Princeton Univ. Art Gallery

The real bridge and water garden were created from Monet's own designs. His painted bridge is a fantasy, too, an improvement on nature and man. And we wish to inhabit Monet's world of seeing because he makes reality better than it is.

2) FLOWERS

Early in his career he chose colorful flowers as subjects, such as in the Poppy Field at Vetheuil in 1879.

.jpg)

Around 1914 at Giverny, as his eyesight grows cloudy with cataracts, he starts to paint canvases where the view

is closer and closer to the flowers until he blocks out the weeping willows, bridge, water and sky; we look down on the lily pads without any other sense of perspective.The white and pink flowers alone captivate his color sensitivities. He transposes the floating plants onto canvas with impasto

blotches of pink, white, and yellow paint. These lilies (called Nympheas in French) dominate his paintings and towards the end of his life are the subject of huge triptychs that sometimes curve, obscuring the view of anything else for the person who sees them in art museums today. The colors become the viewer's focus, a new narrowing that calms and satisfies as prayer.

is closer and closer to the flowers until he blocks out the weeping willows, bridge, water and sky; we look down on the lily pads without any other sense of perspective.The white and pink flowers alone captivate his color sensitivities. He transposes the floating plants onto canvas with impasto

blotches of pink, white, and yellow paint. These lilies (called Nympheas in French) dominate his paintings and towards the end of his life are the subject of huge triptychs that sometimes curve, obscuring the view of anything else for the person who sees them in art museums today. The colors become the viewer's focus, a new narrowing that calms and satisfies as prayer.

Cleveland Art Museum's triptych of Nymphaeas by Monet, 1915-26:

Musee de l'Orangerie's Nymphaeas room, Paris, 1914-26:

3) SERIES of THE SAME SCENE

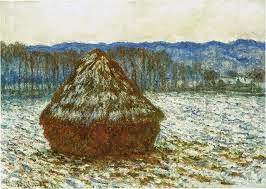

While the Nymphaeas are certainly a series in and of themselves, Monet's obsession with the idea of painting the same scene at different times of day and over and over again begins much earlier. (His painting series has been studied splendidly by Paul Tucker.) Monet painted haystacks, poplars, Rouen Cathedral, and other locations at different points in his career, but always with the intention of conveying the same scene in different kinds of light and weather.

HAYSTACKS: 1890-91, summer and winter (both in Chicago Institute of Art)

POPLARS:

Four trees (Met, N.Y.) Poplars Autumn, Philadelphia Museum of Art (both 1890-91)

:

ROUEN CATHEDRAL:

%2C%2B1892-94%2C%2BMusee%2BMarmottan%2BMonet%2C%2Bparis.JPG)

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, 1894, Full Sunlight Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris, 1894, Sunset

These two Cathedral paintings are only five years before one of Monet's Japanese bridge paintings from Giverny, the 1899 version in Princeton University Art Gallery:

He continues to paint the bridge even up to 1919 when some of his views of it are rendered more abstractly, either because of poor eyesight or because he is influenced by other painters like Turner, Chagall, and Picasso. The arc of the bridge is still there, the willows on the sides, the water underneath but they all swirl together:

London, National Gallery, 1919-20

Musee Marmottan, Paris, 1918-19

His colors in these abstract versions, however, are almost edible they are so lusciously interwoven, dark blue, turquoise, greys, purples.

Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris

In all of his series the painter's desire to reproduce and enhance nature in every season and hour comes across vividly. Monet draws us in with the combinations of colors and makes us question what is deep pond, what is cloud surface reflected in the pond water. And does that matter, if the colors harmonize and cohabit so pleasantly?

In all of his series the painter's desire to reproduce and enhance nature in every season and hour comes across vividly. Monet draws us in with the combinations of colors and makes us question what is deep pond, what is cloud surface reflected in the pond water. And does that matter, if the colors harmonize and cohabit so pleasantly?

Institute of Art, Chicago

.installation%2B(Musee%2Bde%2BL'Orangerie.png)

%2B1890-91%2C%2BChicago.jpg)

-Monet%2BPrinceton.jpg)