BERNINI’S APOLLO

and DAPHNE

Gian Lorenzo Bernini is in his twenties

when he is commissioned to do four different statue groups for Cardinal

Scipione Borghese in Rome. The last of these, begun in 1622 when Bernini is 24

and completed in 1627 when Bernini is 29, is a marble carving of two people out

of one block, the god Apollo and a nymph named Daphne.

Bernini, Apollo and Daphne, 1622-27, Galleria Borghese, Rome

The story is told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses

(1st cent. A.D.), Book 1, and concerns a certain revenge which

is exacted upon Apollo by the god of Love, Cupid. Cupid is mad that Apollo has said that

Cupid’s arrows are not manly and Cupid is thus determined

to show Apollo the full force of his power. He shoots Apollo with a golden arrow

designed to enflame love in him; he then shoots Daphne with a lead-tipped arrow

that causes her to be repulsed by love. What follows is the ultimate story of

unrequited love. Apollo falls enamoured of Daphne, then chases her. Daphne runs, horrified by his pursuit; as he

is about to reach her, she calls out to her father, the river-god Peneus, and

asks him to save her from her pursuer; her father turns her into a laurel tree

just as Apollo is about to touch her. Ovid records this story because he was interested

in transformations, hence his book’s title. Apollo, in Ovid’s version, reacts

to his love’s change into a tree by proclaiming the tree sacred to him and the

laurel leaves the perfect flora for victory wreaths. “Since you can never be my

bride,” he says, which seems an acknowledgement of Cupid’s victory, even though

he never formally tells Cupid himself.

When Bernini decides to sculpt the

statue group of Apollo and Daphne in 1622, he does not include Cupid at all,

but many of Ovid’s lines are realized in the sculptor’s figures. Here are some of the passages of Ovid’s tale

that may influence Bernini’s choices (light blue for Daphne, purple for Apollo):

Ovid on Apollo and Daphne (from

his Metamorphoses, trans. Rolfe Humphries, (Bloomington, Indiana:

Indiana Univ. Press, 1955, 1983), Book I, pp.16-21:

“He would

have said

Much more

than this, but Daphne, frightened, left him

with many words unsaid, and she was

lovely

Even in flight, her limbs bare in the wind,

Her garments fluttering, and her soft hair

streaming,

More beautiful than ever.

But Apollo,

Too young a

god to waste his time in coaxing,

Came following fast. When a

hound starts a rabbit

In an open

field, one runs for game, one safety,

He has her,

or thinks he has, and she is doubtful

Whether she’s

caught or not, so close the margin,

So ran the god and girl, one swift in hope,

The other in terror, but he ran more swiftly,

Borne on the wings of love, gave her no rest,

Shadowed her shoulder, breathed on her streaming

hair.

Her strength was gone, worn out by the long effort

Of the long

flight; she was deathly pale, and seeing

The river of

her father, cried “O help me,

If there is

any power in the rivers,

Change and

destroy the body which has given

Too much

delight!” And hardly had she finished,

When her limbs grew numb and heavy, her

soft breasts

Were closed with delicate bark, her hair was leaves,

Her arms were branches, and her speedy feet

Rooted and held

and her head

became a tree top,

Everything

gone except her grace, her shining.

Apollo loved

her still. He placed his hand

Where he had hoped and felt the heart still beating

Under the bark

and he

embraced the branches

As if they

were still limbs, and kissed the wood,

And the wood

shrank from his kisses, and the god

Exclaimed: “Since you can never be my bride,

My tree at

least you shall be! Let the laurel

Adorn,

henceforth, my hair, my lyre, my quiver:

Let Roman

victors, in the long procession,

Wear laurel

wreaths for triumph and ovation.

Beside

Augustus’ portals let the laurel

Guard and

watch over the oak, and as my head

Is always

youthful, let the laurel always

Be green and

shining!” He said no more. The laurel,

Stirring,

seemed to consent, to be saying Yes.”

It is clear when the text is compared to

the statue group, that Bernini must have read some of the lines in Ovid’s

telling. He carves the bare limbs, the soft hair, the god breathing on her

shoulder. Her hair is sculpted as though turning into leaves, her “speedy feet”

are shaped into marble roots emerging from her toes. (The marble of the roots

is carved to such a thin width in parts, the marble broke and had to be

restored later.)

But the passage of both text and

sculpture that is the most moving because of what is implied is the hand of

Apollo on the bark/skin described by Ovid and carved by Bernini on the abdomen

of Daphne.

He placed his hand

He placed his hand

Where he had hoped and felt the heart still beating

Under the bark

The

sculpted passage of the hand on the bark that is fast covering up the skin

reveals Bernini’s ability to show the woman still alive, with heart beating,

beneath the bark, beneath the marble. It is the beating of the heart described

in the text that Bernini wants to present to the viewer in the touch of

Apollo’s hand on the body of the girl/tree. The viewer is meant to imagine the

pulse.

We see

three layers of marble in this passage:

the naked skin of Daphne, the bark of the laurel that is forming around

her body, and the spread fingers of Apollo carved above the level of the bark. The

beating heart in Ovid means the girl is still alive inside the tree; the

beating heart is what Apollo had hoped to appeal to, the emotional side of her

nature. The beating heart in Bernini is implied by the hand feeling her body

under the bark, a visceral response to touch. For the viewer, the beating heart

implied there also means the marble lives as well as the girl. For a story

about Cupid’s control of love in everyone’s lives, the beating of the heart is

the theme pressed (literally) home by the sculptor. He wants his white block to

live.

When that passage is added to the

other images carved where Bernini manages to transform marble into toes into roots,

marble

into hands into leaves,

marble into

skin into face, marble into curls into hair, the effect is to change not only

Daphne into a tree but the marble itself into figures that are alive in a

landscape. They move through space in rapid flight, one possessed by the desire

for the other, one straining to avoid contact with the other. The tension

between the two and yet their inevitable linking holds the viewer’s attention.

Even Daphne’s beautiful head, which looks back as her mouth opens to call for

help from her father, seems, from certain angles, to move toward Apollo, rather

than away from him, so that the viewer coming upon them in the villa’s room

might have thought them lovers with a different ending.

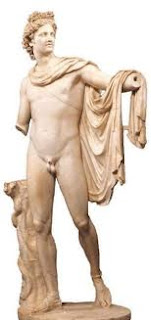

When placed side by side the Apollo Belvedere looks positively staid

in comparison with Bernini’s Apollo, whose weight is entirely on the right leg

and whose left leg is lifted up into the air in full sprint. But they are both

nude statues of the hunter god with drapery and outstretched arms. While the

drapery of Apollo Belvedere is slung over his left arm as it gestures out to

hold what would have been originally a bow,

Bernini’s Apollo has drapery that sways

back behind him at the waist from the wind as he moves through the air. The drapery

over the shoulder of Bernini’s Apollo pushes out into an arc that compliments

the forward curve of Daphne’s body (another way in which they are joined as a

couple).

The head of Bernini’s Apollo is a close

twin of the Apollo Belvedere’s head

as well:

From certain angles the laurel leaves of

the tree Apollo makes sacred sprout, in Bernini’s version, out of his head (2nd

view) as well as Daphne’s; those leaves make Bernini’s Apollo different from

the ancient statue where the feathers from the arrows stand out of the quiver

behind him (1st view) but there is no reference to the laurel. The

same gathering of the sun’s rays on the top of his hair, since he is the sun

god, is nearly identical (4th and 5th views). The same

contrast in texture between skin and deep-cut hair curls is present in both,

the angle of head-turn to torso the same, and the delicate limbs and youthful

body of an excellent athlete are portrayed in both.

But the running of Bernini’s god is what

implies desire; the passion which “moves” him to reach for the maiden in his

hunt. Bernini’s action and passion are the same here and are what differentiate his statue group from that of Leochares.

It is possible that Bernini was influenced by another written source: a

1620 poem by Giambattista Marino entitled “Apollo e Dafne”. Here is the text

and my translation (with thanks to Professors Victor and Ann Marie Carrabino

for their help with it):

Stanca, anelante a la paterna riva, Tired,

longing for her father’s riverbank,

qual suol cervetta affaticata in caccia, Like that sweet doe fatigued from the hunt,

correa piangendo e con smarrita faccia The virgin was running, crying, and with confused face,

la vergine ritrosa e fuggitiva. Bashful and fleeing.

E già l’acceso Dio che la seguiva, And already the inflamed the god who was following her,

giunta ormai del suo corso avea la traccia, By this time having found the track of her run,

quando fermar le piante, alzar le braccia Saw her immediately in the act of escape

ratto la vide, in quel ch’ella fuggiva. Put down roots and raise up her arm branches.

Vede il bel piè radice, e vede (ahi fato!) He sees the beautiful foot root, and sees (oh, destiny!)

che rozza scorza i vaghi membri asconde, What a rough covering the beautiful limbs hide

e l’ombra verdeggiar del crine aurato. And the shadow greening of the golden brow.

Allor l’abbraccia e bacia, e, de le bionde So he hugs and kisses her, and, of the blond

chiome fregio novel, dal tronco amato Tresses a new frieze forms from the beloved trunk.

almen, se’l frutto no, coglie le fronde. At least, if not the fruit, he’ll collect the leaves.

(Italian text taken from terzotriennio.blogspot.com/)

qual suol cervetta affaticata in caccia, Like that sweet doe fatigued from the hunt,

correa piangendo e con smarrita faccia The virgin was running, crying, and with confused face,

la vergine ritrosa e fuggitiva. Bashful and fleeing.

E già l’acceso Dio che la seguiva, And already the inflamed the god who was following her,

giunta ormai del suo corso avea la traccia, By this time having found the track of her run,

quando fermar le piante, alzar le braccia Saw her immediately in the act of escape

ratto la vide, in quel ch’ella fuggiva. Put down roots and raise up her arm branches.

Vede il bel piè radice, e vede (ahi fato!) He sees the beautiful foot root, and sees (oh, destiny!)

che rozza scorza i vaghi membri asconde, What a rough covering the beautiful limbs hide

e l’ombra verdeggiar del crine aurato. And the shadow greening of the golden brow.

Allor l’abbraccia e bacia, e, de le bionde So he hugs and kisses her, and, of the blond

chiome fregio novel, dal tronco amato Tresses a new frieze forms from the beloved trunk.

almen, se’l frutto no, coglie le fronde. At least, if not the fruit, he’ll collect the leaves.

(Italian text taken from terzotriennio.blogspot.com/)

In this version of the story there is no

Cupid mentioned and the description of the scene is much as Bernini chooses to

carve it, making the viewer wonder which came first, the poem or the sculpture.(The fact that Marino repeats the verb

“vede” (he sees) in the third stanza seems a Freudian slip that gives away his

having “seen” the sculpture or a bozzetto of it before writing the poem, in my

opinion.)

The most pertinent passages in the poem that connect to the sculpture

are highlighted in purple:

correa piangendo e con smarrita

faccia (in the marble she

is running as she cries and has a confused face)and the description of the foot

turning into root and the rough bark on the skin:

il bel piè radice, e vede (ahi fato!)

che rozza scorza i vaghi membri

asconde. The foot turning

into a root is the section of the sculpture closest to the viewer when the viewer is

standing below it.

The emphasis in the Marino poem, however, is on the feelings of both

figures and on the futile nature of the hunt; the hunter ends up with leaves

instead of fruit, inedible love-making. The emptiness and waste of the man’s

hunt is what the poet sees as the moral since the poet imagines the definitive

end of the chase.

Bernini, on the other hand, chooses the moment before the end, the

moment of greatest tension and greatest movement, the apex of the hunt, before

it closes down. That way the viewer still sees the human beauty that envelopes

both the protagonists. The lifelike quality of both Apollo and Daphne, the

youthfulness of their heads, and the loveliness of their figures in motion all

contribute to Bernini’s riveting scene, the moment when she is about to turn

into a tree, the moment when Apollo is about to reach her, the moment when the

chase is about to be over. Bernini chooses that moment, not the moment when her

change into tree is completed, not the moment when Apollo spies her, not the

moment when she is alone in the forest, before she runs from the god.

The apex of the action is what is appealing to him because it is before

the action stops. In this way his art can continue to live. She will never

fully be a laurel tree; he will never fully grasp her as a tree. Apollo is most

alive in his pursuit; Daphne is most alive in her flight before the roots take

hold and she is immobilized by ground and bark.

She will never lose her youthful beauty that made him love her in the

first place; he will never lose his youthful power that made her fear him. The

energy conveyed by Bernini in the movement of the drapery and hair and limbs of

the figures will continue to surge even after this century is gone; he has

understood that the electricity between the figures will be eternal, he has

understood that his art will continue to represent the fleeting moment in time

eternally. The capturing of the maiden

is not the art; the almost capturing of her is.

She can never die in this sculpture; she and Apollo are in marble the

essence of what they are in the myth, nymph (daughter of a god), and god. They

are caught in youthful beauty in the timelessness of all the gods and Apollo

also in a human timeless longing not only for love but for youth itself.

The viewer is caught, too, in the beauty that Bernini creates that nourishes

no matter how many times a person revisits. In that way the metamorphosis that is

taking place in the sculpture is mirrored in the viewer. We are transformed by

the vision that he presents of what sculpture can achieve, the vision of beauty

caught in a story where the beautiful nymph is not caught, a vision of the

capture of movement in a material that seems unwieldy and unmoving, the capture

of realistic materials in a material that appears unbendable. The unrequited

love then is also the wish of the viewer to be those figures, be that beauty,

be young again forever.

For Bernini art is metamorphosis, the transformation of marble into

human beings, into hands, toes, fingers, hair, eyes, legs, then transformation

into nature: tree trunk, tree bark, tree leaves, branches, and roots, and

finally drama. But Bernini’s transformation always includes beauty of form. If

you compare his work with painted images of the same story in early periods:

i.e.,

Pollaiuolo’s Apollo

and Daphne of 1470-80 in the National Gallery, London:

or Domenichino’s Apollo and Daphne painted for the Aldobrandini villa in Frascati

from 1616-1618, now in the National Gallery in London, too, the distance

between the figures is, in the first example, too close and, in the second, too

far away. Like the bed finally decided upon by Goldilocks, Bernini’s is just

right. In Pollaiuolo’s the branches of the laurel tree that emerge from

Daphne’s arms look like two pompoms on a cheerleader being lifted at a football

game. In the Domenichino example, she almost looks back at him as if to say,

“What’s taking you so long?” because the space between them is too great. Only

Bernini understood the importance of proportion in the bodies of the figures

and in the space between them. These two painted images seem laughable when set

next to Bernini’s sculpting.(Domenichino's fresco is noted by Bruce Boucher, Italian Baroque Sculpture, (London: Penguin, 1998).

But what Bernini also understood that these two painters did not is that

if you are making a work of art about desire and love, you must carve physical

beauty into the figures so that the viewer will understand why the person

desired, why the person was loved in the first place. Both Apollo and Daphne in

his version are peerless young people and the viewer’s desire to be nourished

by looking at them is evident when groups of people who stop in front of them

cannot leave; they are transfixed as though they are the ones turned into trees. Beauty is nourishment, and Bernini nourishes with his whole heart

and soul in this statue group, mesmerizing the public. In his skillful hands

the dramatic moment comes alive and the metamorphosis continually recurs. What doesn’t change is the nature of

desire, and our desire to view beauty is, in Bernini’s sculpture, a love

requited.